Reflecting on the Book “Own Your Greatness”

I’m a writer. Actually, I answer 9-1-1 calls in Cincinnati and write articles and web copy for a few small companies locally and across the United States. Before that I was a teacher and a principal for 25 years.

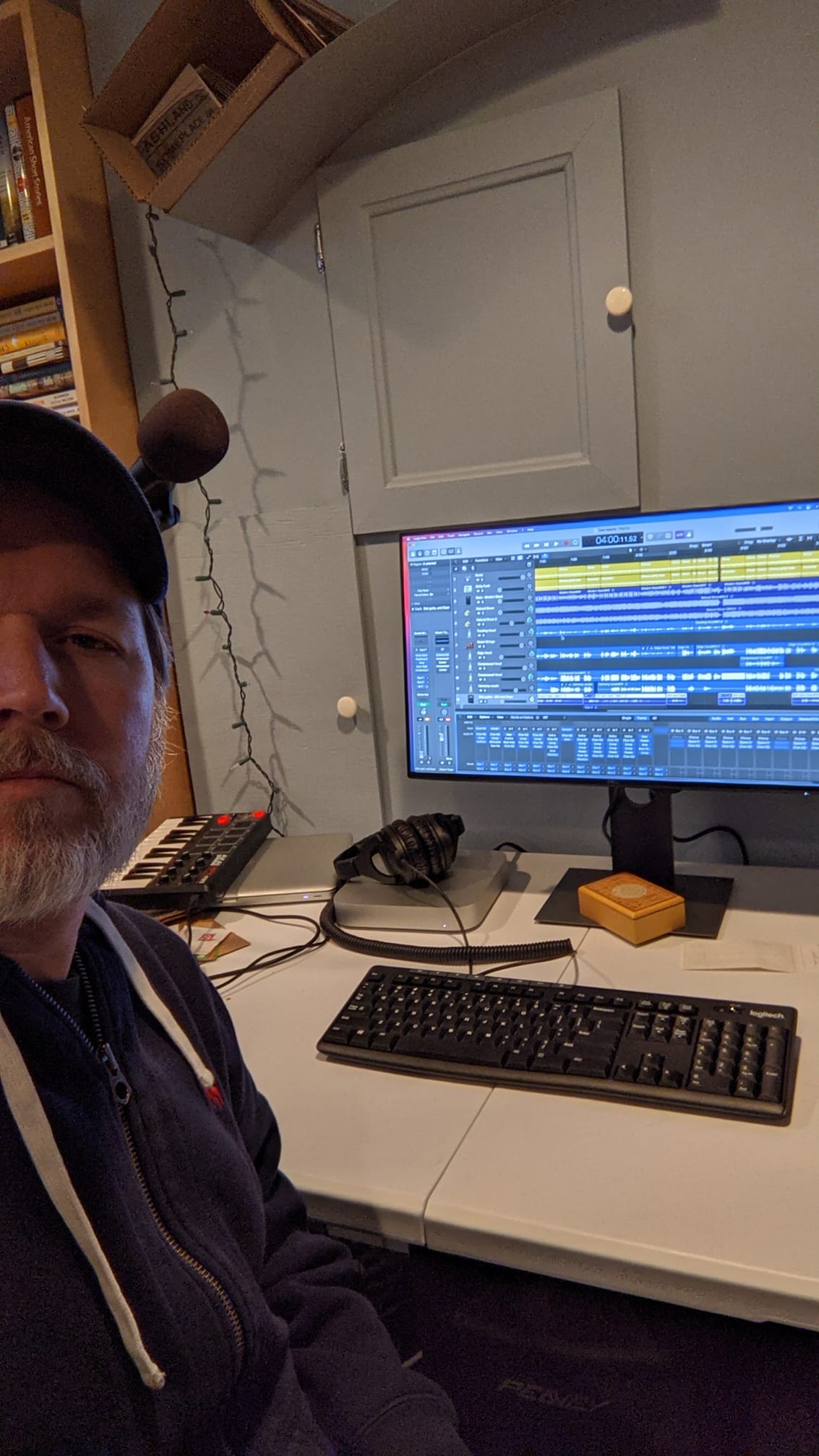

But, if you caught me in an unguarded moment, and I was truthful, I would tell you I am a songwriter. I am a poet. I love words. I enjoy setting them to music. I just didn’t have a practical road to making a living as a songwriter when I was young, so I went into a field that interested me – teaching English. It allowed me to submerge myself in language, and celebrate the joy of learning something new.

Language and learning are truly my passions.

But why don’t I ever play my music in front of people? Why do I labor in my basement over songs I share with two or three people over a lifetime? Then post these songs to relative obscurity on streaming platforms available to everyone? And it pains me to admit it, but I am also a great consumer of my own music – I showed up in the top 5 of my own Spotify wrapped list. I doubt that happened to Beyoncé.

In large part, I think my unwillingness to play and perform for others is because I think I can’t do it. It is because of a belief that because I did not grown up in music, because I did not study an instrument after high school, or get formal education in music, because I do not have years of experience doing the work of a musician, I am an imposter.

I look at the most accomplished songwriters of the last couple of generations (and the list is incredibly long and diverse) and I conclude, “I couldn’t do THAT. Somehow THAT is different than what I am doing.”

In part, I am right. It does take experience and training to be really great at something. It certainly helps to have years of experience, formal training, and to be surrounded by great artists and producers. And maybe to have your Grammy-winning brother as your live-in producer. That has to help.

But in part, I am wrong. Significantly so. Everyone starts somewhere. And my passion for language — a life-long passion — has in fact prepared me well to craft and choose words in an intentional way. This is the heart of songwriting.

What is holding me back is a belief that I can’t call myself a songwriter because I have not “earned it.” But when I say I haven’t “earned it,” I mean that in some inscrutable way I can’t define, because I’m not an expert in the field.

What is holding me back is imposter syndrome.

“Own Your Greatness”

In their book “Own Your Greatness,” psychologists Lisa and Richard Orbé-Austin aim to help people tackle imposter syndrome. And, truth be told, the book title was a bit of an obstacle. That seemed quite a leap to go from “I am an imposter” to “own your greatness.” I was pretty sure I needed a book like “own your mediocrity” to sort of get me over the hump to where I could think about the steps to greatness. I needed to study “On the Road to Averageness,” “Making Peace with Occasional Okay-ness,” and perhaps someone should write the book I would buy in a heartbeat: “Get Yourself to ‘Hey That Wasn’t Half Bad.’”

But “Own Your Greatness” was the book in hand. Here, Drs. Orbé-Austin describe steps to overcoming imposter syndrome. Steps that I will endeavor to outline and follow in my quest to become a songwriter.

They outline seven steps to overcoming imposter syndrome. I explain them below, and provide some personal examples. That is I will endeavor to describe my own efforts to be a songwriter while sabotaging and undermining my progress toward becoming a songwriter.

I hope this helps someone else struggling with imposter syndrome.

Tell your imposter story

Step one is to tell your imposter story, to make it obvious. This is to enable you to fight the infection by exposing it to sunlight. I started this in the introduction. There, I told the story about myself. And at the heart of it, the psychology of it, is that I believed two things that contradicted each other. First, I believed that if I was really gifted at something, it should come easily. This was definitely not the case with the violin, then the piano, and then the guitar. So it was easy to dismiss my struggles there not as evidence of learning, but as evidence of inadequacy.

But the other deep belief I learned growing up was modeled on my mother’s work ethic. She demonstrated daily that getting up and going to work every day was a key to success. This was perhaps her most sincerely held belief. I hold that belief too. And applying it to my imposter syndrome may turn out to be part of the cure.

The authors insist that by telling this story, by writing this down, I have started the path to defeating my imposter syndrome. I hope they’re right.

Know Your triggers

Step two is to know your triggers. Triggers are those situations that activate or intensify your imposter syndrome. There’s an open mic Sunday? Trigger. A friend invited me to a guitar playing circle? Trigger. Hearing a Brandi Carlile song that is impossibly well crafted and beautifully performed? Trigger. Watching a friend and his band play at a local bar? Trigger.

Each trigger has its own responses which happen automatically. Now that I have identified some of the triggers, the authors suggest I need to examine my responses, then condition my responses to deal with each one.

They suggest writing a “coping card” for each trigger. By looking at these situations and looking for patterns in my responses, I can identify what I was thinking or how I reacted, and then with the coping card, I can teach myself to react differently in these situations.

In my case, the pattern for me is avoidance. For the open mic? Well, I immediately remember times I performed poorly or things didn’t go well, notes I missed or banter that was boring or didn’t add to the performance. I recall the way the guitar sometimes will suddenly feel foreign and oversized in my hand, like a strange new instrument. I decide that I will be busy at that time and unable to go to the open mic. Watching a friend play in a local bar or hearing that perfectly-crafted song? They make it look easy, and unrehearsed. I can immediately identify the ways they are better than me at singing and playing guitar. That might spark entire days where I can’t pick up my guitar or sit in front of the mic to record anything at all.

These are my triggers, and these are my responses. I won’t write each of them, but I do see that my pattern is avoidance.

Change Your Narrative

So in these cases, I need to take my tired old story and craft a more positive narrative. The authors call this “thickening the story.”

For every one of us experiencing it, our imposter stories leave out a lot of context and detail. For instance, sure I remember times when I played a song poorly, forgot the words or chord progression, and the way my beating heart seemed to drown the guitar. That was terrible. That happened in front of people who I care about, and whose opinion is important to me!

That is a thin story. That DID happen. But it is not the ONLY thing that happened to me as a songwriter. To counter that, I need to remember one of the happiest moments of my short stage career. One time I started “Back Roads Home” and the talented Molly Morris-Wickizer of the local band Harlot turned to her husband and said, very clearly, “I love this song!” I presume she had heard the song multiple times because her husband recorded, mixed, and produced my first album. (Here’s a link to my first album on Spotify.)

And I know my friends and the veteran musicians I so admire have in fact spent countless hours performing. Aaron Hedrick, who started the open mic at Wunderbar where I first got up the nerve to perform my songs, has played regularly multiple times a week for longer than I’ve known him. (Here’s a link to his Spotify page where he records as Working Class Villain.) Blake Taylor, who recommended Wunderbar to me, has a standing monthly gig as half of the band 46 Long at a popular downtown bar. (Here’s a link to their Bandcamp page.) They aren’t “making it look easy” by just getting up and doing it the few times I see them. They are in fact practicing or playing together alone and in front of audiences multiple times a week. And they all started somewhere. That means they all had a first time, and a second.

And of course I know that 46 Long, Mike Moroski, and John Lewandowski would never have let me play during their breaks in their sets if they didn’t have some amount of confidence in me. Dan Sanchez and the folks in his guitar circle invited me back, so that’s something, right?

Thickening the story allows me to affirm that I am like these people I so admire. I belong with them. I am just at a different spot on my path. They are further along than me. My work is to take the next step, and to remember that every time a trigger makes me want to stop playing or writing or recording.

Speak Your Truth

You can’t overcome your imposter syndrome alone, the authors assure me. But alone is where I am most comfortable!

They suggest sharing these feelings with a couple of people who you trust most deeply in your life. Share your feelings and triggers, and their effect on your performance and feelings.

Your friends and confidants will likely share their own imposter syndrome stories, and times they felt inadequate.

Or, if you’re lucky, you will have friends like my son, who when I shared my feeling with him, said, “Dad, you ARE a songwriter. You’ve done this. There are albums of your songs, and even more you haven’t recorded.” And my friend DaShawn Glover who writes, performs, and records under the name D Glove. (Here’s a link to a Youtube feed of some of his songs.) I recently wrote a song over a beat he created, but I also shared my imposter syndrome feelings with him. Now every day he greets me by saying, “You’re a songwriter!”

This is powerful medicine.

By thickening the story, I am acknowledging that I actually have skills and talents. This can include skills that relate to or support my songwriting, that aren’t necessarily the equivalent of winning a Grammy or recording in a professional studio. I can play all of the guitar chords needed to write a good song. I have a rich series of life experiences — mine and others’ — from which to draw stories and lessons. I have a pretty big vocabulary.

I have the tools to achieve my goals.

Avoid the ANTs

Here the authors describe a condition with which I am deeply familiar. They say that everyone has some Automatic Negative Thoughts, or ANTs, created around their imposter story.

Some of these for me have come up already while I was thickening my narrative. The authors suggest there are some superhuman and subhuman skills that our ANTs have acquired. Here are some things everyone’s imposter syndrome allows their brain to think it can do:

- Mindreading – can your automatic negative thoughts tell you that other people think you’re bad at what you’re doing? Really? They can read minds?

- Labeling – do your ANTs call you names and put you down? Who let them do that?

- Fortune telling – Oh, your imposter syndrome can tell you exactly the terrible way this will turn out

- Catastrophizing – this is going to lead to embarrassment or ridicule, or things will catch fire, and people will laugh or … well, insert your big fear here

- Unfair comparisons – well, you’re no Brandi Carlile; but on the other hand, you’re also no Jason Isbel; further, you’re not Pat Hu or Dan Van Vechten

- All or nothing – if it’s not perfect, then it doesn’t count or doesn’t matter; for example those nights I screwed up, well, those weren’t hardly even experience

- Discounting positives – that praise is just kindness, it is not genuine praise. They don’t want to hurt my feelings because I’m a nice guy and I try hard

The two strongest ANTs for me are “unfair comparisons” (Brandi Carlisle? Really?) and “discounting positives”, with a shout out to “all or nothing.”

The authors suggest I should develop “ANT repellant” by asking challenging questions of each ANT. They direct the reader to write out a list of challenge questions for each ANT and write a replacement thought, which they call a repellANT. I guess it also works as a disinfectANT.

For example: If I make a mistake … I won’t be ridiculed or laughed at. And talking to people after a performance gives me a chance to get meaningful feedback from experienced professionals. Recovering from a mistake is actually the best way to learn to perform, and that also gives me the confidence to continue to share my music.

“Unfair Comparison” repellant:

Let’s talk about famous songwriters. There is no magic sauce. Bruce Springsteen recently said that the decades-old story that he wrote a song every day when he was young was false. Sigh. The idols fall.

Brandi Carlile said this in an interview at songwriteruniverse.com

“Essentially, I’m not much of a songwriting workshop instructor type of person, because it really just happens to me. I don’t even know how or why or where, and sometimes it doesn’t happen for years at a time. I’ll go two years without writing a song. But when it happens, I’m just kind of witnessing it, you know. It might just be, I sit down at the piano and play a chord that I’ve played everyday for the past 20 years. But today for some reason, the chord is a song, and a song comes out. Or I wake up in the middle of the night and reach over and grab a pen and paper and start writing a story, or writing poetry. And then the next morning, the chords come to me. It’s like something that just comes through. It’s all about recognizing that it’s trying to come through, and being able to stop whatever I’m doing and let it happen.”

And what about the “overnight success” of a star like Lil Nas X and his smash “Old Town Road?” Well, it didn’t happen by magic. And it only seemed to us to happen overnight. As he explained in an interview for Stereogum.com: “I promoted the song as a meme for months until it caught on to TikTok and it became way bigger.” Which is, of course, it became the most streamed song of all time.

But who am I anyway, to compare myself to luminaries? Isn’t that the most bizarre, wrong-headed sort of imposter syndrome deception? Am I really not a songwriter if I don’t write the most streamed song of all time? Literally every songwriter except one shares that ignominy. Maybe I can be okay with not achieving a goal that none of my favorite artists have achieved? Moving units is not what a real songwriter does. A songwriter doesn’t necessarily have to win accolades to be excellent at what they do.

And doing a good job without being recognized as the best is a concept I know quite well. In 25 years of education I only worked with one individual who was ever officially named “Teacher of the Year,” and a handful ever nominated for such a title. But I knew in reality dozens of individuals who sparked a love of learning in others, who taught without demeaning or controlling students, and who played important roles in their students’ lives. These were real teachers, perhaps considered angels or superheroes by their students, who never received singular recognition for the important work they were doing every day.

I need to stop making unfair and unrealistic comparisons, and focus on getting better at my craft. I just need to do the thing.

Discounting positives repellant

Of all the ways I undermine myself, this is the most painful to admit. The fact is, I have purposefully sought out and connected with people who are supportive. I have experienced a great deal of personal and professional success in my life, and I owe it in no small part to my practice of gravitating toward people who I trust are trying to support others in a conscientious way. By extension, I know that these people will support me and offer meaningful, helpful feedback.

When I was first thinking about places to play my songs at an open mic, I asked for (and received) the name of a place that was renowned for being supportive and encouraging of artists. Wunderbar was – and remains – incredibly supportive and everything I was told it would be.

And yet when the songwriters there offered praise and support, in my mind I dismissed it. When one patron’s head nodded approvingly during a song, I wrote it off as a coincidental response to an unrelated question or conversation. Then, when a gifted guitarist offered encouragement, I thought of their superior skills and told myself they were merely being charitable.

When people whose opinions I value and support called me a songwriter and offered appreciation for my work – praise and encouragement I longed for – I dismissed it all too often. Then I even specifically asked for feedback from other people I admired. If they didn’t offer feedback, or didn’t respond to an email, I took it as criticism.

In short, I created a situation where I could not possibly win. No praise was good enough for me to accept.

Sadly, this is even true when I received the highest praise I’ve ever gotten. Sons are not known for, or needed for, offering their fathers support and encouragement. As I described earlier, my son Ben gave me praise that was specific and factual – the most solid praise a person can offer. You would think this would get through my ANTs. He pointed out that I’d put together two albums of actual songs, available to most music listeners, each of which have all the symptoms of being real songs … even then, even as I was floating on the unexpected praise of someone whose opinion on music quality I trust completely, I did not take that as a reason to believe in myself.

This was hard to admit. Why would I reject the words of people I trust and respect? Why reject even the praise from my son?

I am my own worst enemy.

So then, what is my “discounting positives” repellant. What do I need to tell myself to get past this?

The folks at Wunderbar have been making music alone and together for years. They’ve been paid to make music, invited to perform for audiences, and they’ve recorded albums. They know what they are talking about. These people I’ve mentioned make good music and perform it admirably – that’s not easy to discount. Sons aren’t prone to light praise. I should believe that.

I should see that the facts are that I can do this, and I’m competent at it, as shown by people who know. And I should not disrespect those opinions and those people by not moving ahead and continuing to do the thing I love.

“All or Nothing” repellant

I already know how unrealistic the bar I’ve theoretically set for myself is. Every songwriter the average music listener can name has achieved a high level of songwriting and performing. And a lot of successful songwriters earn a living in relative obscurity, their names never spoken except by those in the industry.

I also acknowledge the irony of trying to repel the “all or nothing” belief in a book called “Own Your Greatness.”

Big goals are reached only by setting and reaching little goals on the way.

I need to reject the “all or nothing” automatic negative thought. And I’m surprised to learn as I read this book that I’ve already taken an important first step to address this.

Late last year I confronted myself a little bit on my periods of inactivity toward my goal, and I remembered the steps it took for me to reach any of the goals I’ve achieved. I never set a goal that was dependent on what others thought or how they reacted to my work. Instead I’ve always set goals that are really steps for getting to where I want to be.

So in November I set out some goals for myself that weren’t especially time bound, but were generally sequential – and not one of them are related to the aspects of success that are out of my control.

My “all or nothing” repellant is setting goals that are almost entirely in my control. Well, not entirely. The goals grow more audacious as the list proceeds. But it is okay to set audacious goals and carry them into the future, as long as you are making progress.

Experiment with New Roles

Step 6 of owning your greatness is to experiment with new roles. This is about giving up your existing roles and replacing them. Here are some examples of common roles played by people with imposter syndrome. Many of them are directed towards folks in business settings, but some might apply to aspiring songwriters …

Role: Helper – always there to help others meet a deadline, solve a problem, finish a task. This person is everyone’s favorite person at crunch time

Replacement role: Person requesting help – start small and ask for something you need, or ask for support with your own project. Ask someone who has asked you for help before.

Role: Super person – you can do it all on your own! You can handle all the responsibility! You can leap tall buildings and never need an ounce of assistance!

Replacement role: Delegator / collaborator. You’re the one who can assemble a small team to tackle a problem. You know that enlisting others to help builds your capacity as a leader. It doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to be done (by someone else).

Role: Failure avoider – Are you the person who fears making a mistake, being embarrassed, not doing a thing perfectly? Does it feel scary just to think about making an error?

Replacement role: Risk taker – Take a calculated risk. Try something new. Start small. Don’t redesign the company, just tweak a little something in your neck of the woods. Write and share a bad song, or a rough draft.

Role: Behind the scenes leader – the leaders all depend on you to do heavy lifting … until it is time to stand in the spotlight, or put a name on a finished product.

Replacement role: Visible leader – again starting small, step up and take a visible leadership role. When someone needs to present the idea, let the team know that this time it will be you.

In all of these cases, the authors caution us to try out the new role on a small scale. The work is this: list one of these new roles and plan how you will take that next step.

And for me, the role I play is clear. I am a failure avoider. I can’t screw up on stage if I am never on stage! People can’t hate my songs if they never hear them! (But do people ever really hate a song? Other than, of course, “Last Christmas?”)

So now I need to step into a role I have not been afraid of in the past in my other endeavors. Here I need to become a (calculated) risk taker. I need to do the things I have been afraid to do.

Michael Stipe to the rescue: “How can I be / What I want to be? … I’ll trip, fall, pick myself up and / Walk unafraid / I’ll be clumsy instead / Hold me love me or leave me high.”

It’s mildly encouraging to remember that lyric comes from a largely overlooked R.E.M. album called Up.

Build Your Dream Team

This is seventh and final step or “coping card” to counter imposter syndrome. Construct a team of people who are dedicated to helping you defeat your imposter syndrome. The authors suggest that you will want to find people that fill these important roles on your team, who are in charge of specific tasks or responsibilities as indicated below.

The first step is identifying the roles, then listing 1 or 2 people who can perform each role when needed.

- Cheerleader – can lift you up when you are feeling low or when you suffer a setback

- Grounder – can give you a reality check; requires a rational, honest broker to speak up when you are spiraling

- Action planner – this person is good at solving problems and can help you break the goal into steps

- Big picture person – this person can remind you of your values and where you want to go in life and how the steps contribute to your objectives

- Imposter expert – a friend who either has battled imposter syndrome themselves, or a professional coach or therapist who can spot where the imposter syndrome is blocking your progress

- Mentor – person who is experienced in the field who can help you navigate or advance in your career

I’m not listing who I will ask to fill these roles to me, because that is personal. And besides, it sets me up for failure if they say no, or it sets them up to feel obligated if they read this.

I will admit feeling like I can play a lot of those roles myself. For instance, I am a pretty good person to think from a big picture back to action steps. However, I know that not filling each of these roles with a different person is a cop out.

Most importantly for me, I am pondering someone to approach to be my songwriter and performer mentor. I have a few good prospects and there is much to consider. This might be the most important member of my dream team, especially in terms of getting me out of my comfort zone.

I commit to putting together a team to combat imposter syndrome. The better prepared I am, the more success I am likely to find in an area where I genuinely want to be successful. For me, being successful doesn’t mean a million streams. (But is 30 too much to ask?) It means working toward my goals and reaching out to people dedicated to helping me stay focused and accountable. I look forward to the challenge and the music ahead.

Well, thank you for making it this far. Is there some part of your life where you experience imposter syndrome? Did you cringe along with me as I admitted my own? Were any of the tips helpful? I’d love to hear about it.

Comments

One response to “Overcoming Imposter Syndrome: A Songwriter’s Confession and Pledge”

From one impostor to another: you already excel at being a writer, as evidenced by this post. As a cheerleader, I say just put “song” in front of “writer” and you are already there.